Published on 03.12.2019

Why do some people go out to meet others more easily? Can we explain the fact that some people seem more comfortable in society? For several years neurosciences have explored these fields and tried to establish links between behavior and physiological data.

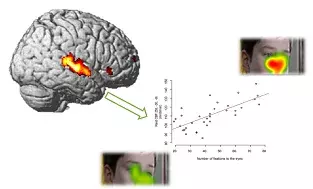

The team in charge of this study looked for the possible existence of a cerebral basis to these differences and if there was a way of detecting them. This team used measures of gaze behavior (eye-tracking) and magnetic resonance brain imaging (MRI). By analyzing the gaze of young adult volunteers when watching scenes from the film “Le Petit Nicolas”, the study showed, for the first time, that the way of looking at presented social interactions varies greatly, and that there is a meaning behind this: there are those who look in the characters’ eyes a lot and those who look in them very little, which reflects the social behavior of each of them.

This way of looking at the other is unique to each individual and does not change over time. “It is a sort of individual signature of the level of sociability”, notes Ana Saitovitch.

To try to understand the brain mechanisms that underlie these different behaviors, the team then quantified resting brain activity in the same people, with an MRI and separately from the viewing of videos, by measuring cerebral blood flow.

A significant correlation was recorded between the number of times where a person looks in the eyes and the resting blood flow only in a very specific region of the brain. This is the superior temporal sulcus (STS), which is a key place in the brain for social cognition. Therefore, people who look in the eyes of others a lot are those who have a more significant resting brain activity in this region. On the other hand, those who look less in the eyes of others have a less significant activity.

This work has helped to establish different brain signatures unique to each individual, which determine the level of sociability.

These innovative results provide new ways of understanding the variability in social behavior and its neural substrates. In addition, they could contribute to a better understanding of diseases that have an impact on social behavior, such as autism spectrum disorders.