Published on 12.08.2021

If from the outside, vertebrate animals appear symmetrical on the right and on the left, on the inside it is quite different: on the one hand the position of the organs in the body is asymmetrical, and these same organs are often themselves asymmetrical.

The heart, the first organ to start functioning, is a favorite subject of the Heart Morphogenesis laboratory directed by Sigolène Meilhac at the Institut Pasteur and the Institut Imagine. With her team, Sigolène Meilhac is trying to find out how it forms and how this asymmetry is established. "This is an especially important question because the shape of the heart determines its function," explains the researcher.

One Heart, Two Pumps

The heart can be likened to two pumps: the right pump that sends oxygen-poor blood to the lungs and the left pump that distributes oxygen-rich blood to the other organs. These two cardiac compartments must be completely sealed. Otherwise the blood mixes, and oxygenation is insufficient for the proper functioning of the organs.

This partitioning of the heart, which ensures the double circulation of blood, is based on an asymmetric event that takes place in the embryo during the first 20 to 28 days of pregnancy," notes Audrey Desgrange, post-doctoral fellow in the Heart Morphogenesis Laboratory. At this time, the heart's outline is a tube, and it will curl up a bit like a snail's shell helix. This step is fundamental to the alignment of the heart chambers and the partitioning of the heart."

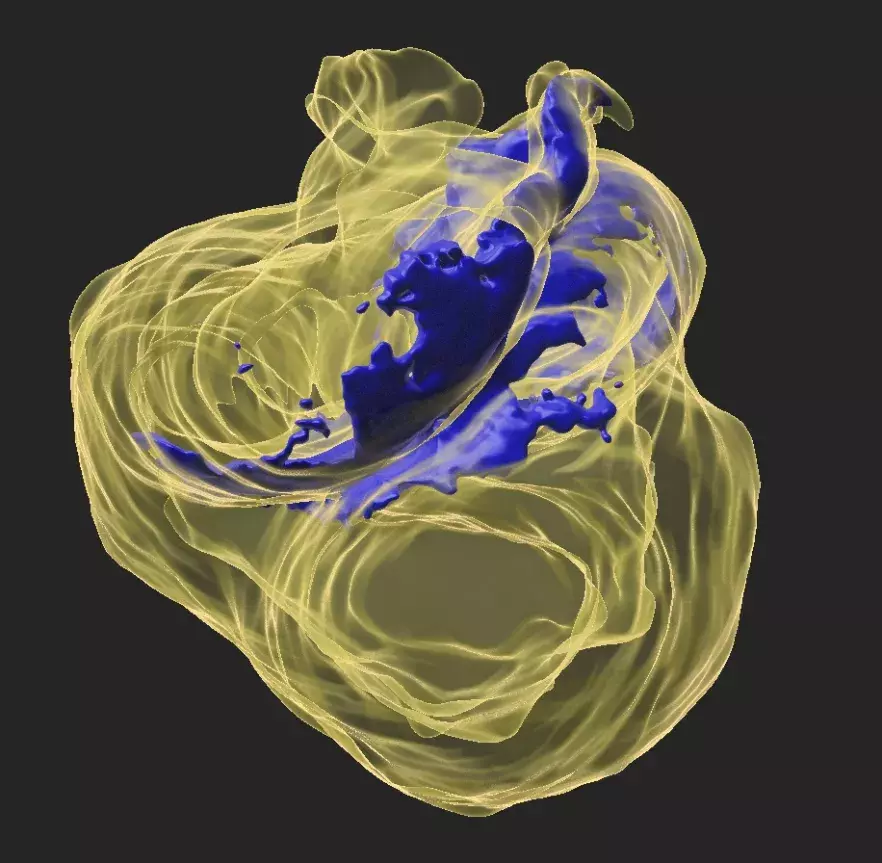

In their latest publication in Developmental Cell, Sigolène Meilhac's laboratory observed this tube transformation in the mouse embryo in 3D, by following in particular an actor of the asymmetry, the Nodal gene. Nodal has long been known to define the left side of the body," recalls Sigolène Meilhac. We observed that its action was transient and early in the heart cells, before the heart starts beating.

In the absence of Nodal, the embryonic heart tube is still curved, but the helix is askew, which leads to heart defects at birth, characteristic of the heterotaxy syndrome. "To understand why the helix was abnormal, we combined computer simulations and state-of-the-art molecular analysis," describes Audrey Desgrange. While the initiation of heart asymmetry is independent of Nodal, it does play an important role: it orients and sculpts the curvature so that the embryonic heart tube takes on a helix shape.

Although this work shows that Nodal is not the only regulator of asymmetry, its role remains major in the final partitioning of the heart, which is necessary for the establishment of the blood flow.

The researchers are therefore continuing their exploration of the embryonic heart with the idea of demonstrating the origin of congenital malformations of the heart and thus contributing to better patient care and information for families.